Research

Click on each below to learn more

The APF A-star Retirement Program (AARP)

Subgiant stars (slightly evolved stars) are a relatively understudied population in planet searches, but represent a unique sample for probing how stellar evolution and stellar mass affect planet demographics. The "Retired" A-star program monitored the radial velocities of a sample of subgiants for nearly two decades with Keck-HIRES, discovering mroe than 50 planets orbiting such stars (see my 2019 paper here for some recent discoveries/candidates).

As my thesis work showed, evolved stars are dominated by stellar variability driven by convective motions, specifically p-mode oscillations, the global surface deformations that result from convection-driven pressure waves that travel throughout the interior of the star. These p-mode oscillations can have amplitudes 3–10 m/s, indicating that the residuals in the RV time series of subgiants are dominated by stellar signals; we've hit an astrophysical floor that could be drowning out the signals of any companions less massive than Neptune/Saturn in these systems!

Luckily, p-mode oscillations have a well understood temporal structure, with characteristic cycling behavior on timescales that are closely tied to stellar parameters (effective temperature and surface gravity). For dwarf stars, we can mitigate the typical ~5 minute oscillations by choosing sufficiently long exposure times that average over the p-mode period. For subgiant stars—with sometimes hours-long cycles—this strategy simply isn't practical.

Instead, I've devised a new survey strategy for evolved stars that aims to leverage the anticorrelated nature of p-mode oscillations, by precisely spacing two observations in a night. By taking a second exposure separated by exactly half of the dominant p-mode oscillation timescale, the observations will bin down faster than typical sqrt(N) white noise, allowing us to probe below the p-mode floor.

We have implemented this approach on the Automated Planet Finder (APF) telescope, a fully robotic telescope at Lick Observatory dedicated to RV observations. It's robotic nature allows us to specify the unique intra-night cadence for each star, according to its p-mode oscillation timescale.

We're calling this survey the APF A-star Retirement Program (AARP), and the goals of our program are to:

- STRETCH OUT:

Extend the baseline on ~35 planet-hosting subgiants (long-period companions) - REVIVE:

Re-establish high-cadence observations now with APF (short-period companions) - RELAX:

Remove jitter with tailored observations to capture and bin down stellar oscillations

We have a year of observations under our belt and our results show promise. APF has demonstrated excellent ability to achieve the desired intra-night cadences within +/-10 minutes. Our initial results indicate moderate improvement over HIRES and more importantly appear to perform better than the expected sqrt(2) reduction one would expect from 2 randomly separated observations in the night, assuming a white noise component.

We're excited for the future of this program and the discoveries it will enable. Stay tuned for a first write-up of the survey and initial performance!

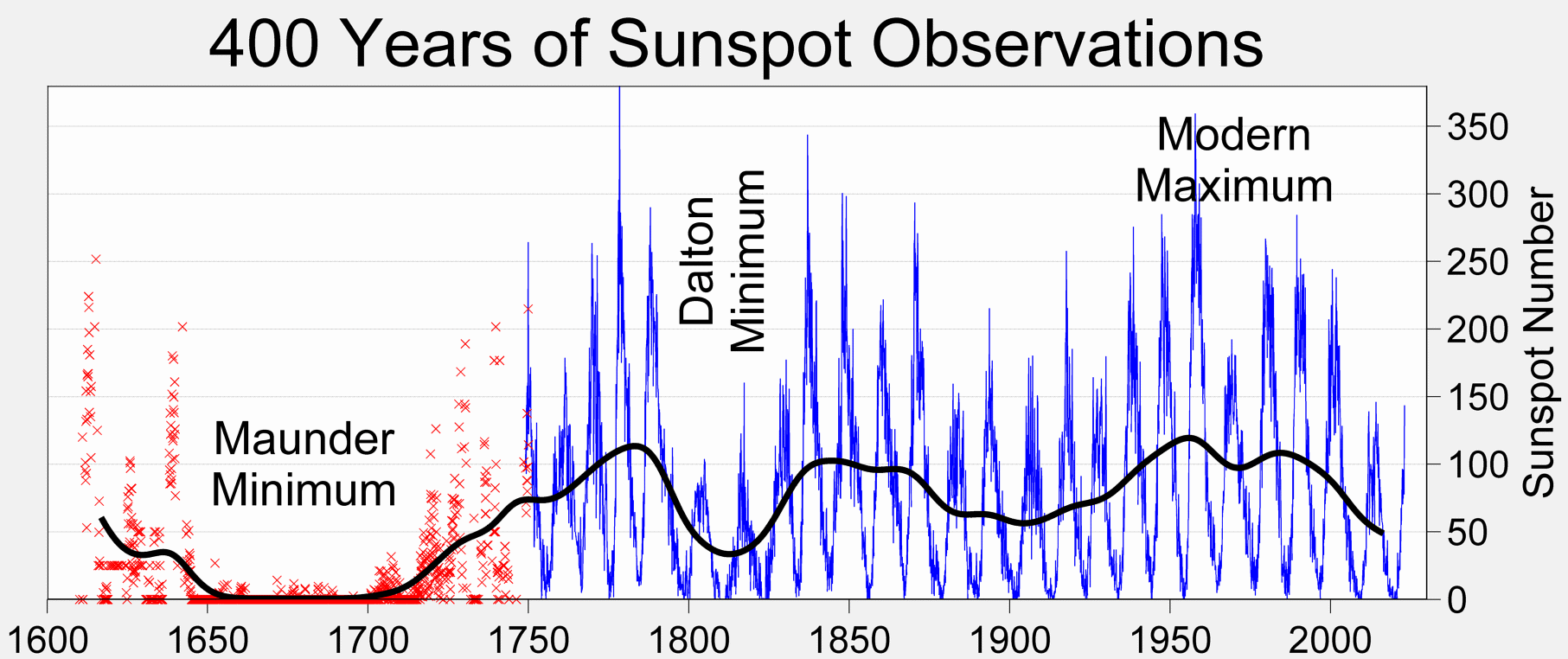

Maunder Minimum Star HD 166620

The Sun has an 11-year magnetic activity cycle, which can be traced back for centuries as seen in sunspot records. But there was a mysterious span of about 70 years (1645–1715) where there were significantly fewer sunspots, and its cycling behavior appeard to stop. The cycle picked back up shortly thereafter and has happily continued cycling ever since.

What caused this "Maunder Minimum" (named after the solar astronomers Edward and Annie Maunder) remains unknown. It is an especially challenging problem to study given the timescales involved: our best knowledge comes from a 70-year period in a 400-year timespan. We can't just wait around and hope the Sun falls into another Maunder Minimum span.

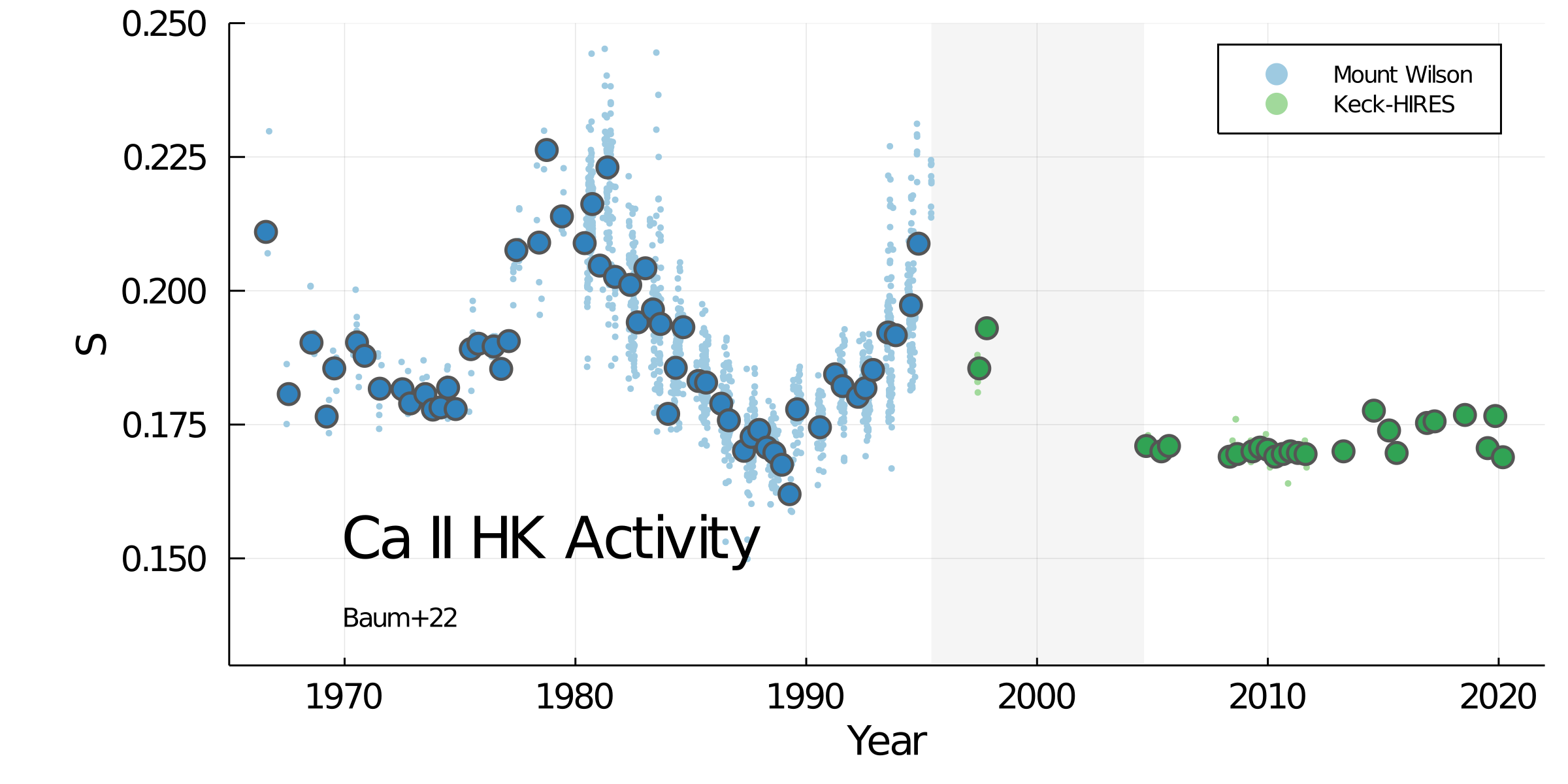

Instead, we turn to other stars. By observing many stars over decades, we can essentially build up a similar time baseline across all of the stars, and hope to catch one in a non-cycling state. This was one of the goals of the Mount Wilson Program, which was begun in the 1960s studied the activity levels—a proxy for star spots for stars where we can't resolve their surface features—for 100s of stars.

While there have been some Maunder Minimum candidates proposed from those observations, many turned out to simply be slightly evolved subgiant stars, which in their old age become very slowly rotating stars with very little activity at all. This adds additional complications to the problem: non-cycling behavior alone isn't enough. What would be better is if we could see a star go from cycling to non-cycling, which considerably lengthens the necessary time baseline to make such a discovery.

The California Planet Search helps in this regard; although it is an RV survey searching for planets around nearby bright stars, activity measurements come "for free" as part of their observations. We therefore continue to build on the legacy of the Mount Wilson Program with additional coverage time series that in some cases spans over 50 years of observations.

Enter Penn State undergraduate student Anna Baum (now a graduate student at Lehigh university), who set out to properly unify the Mount Wilson Survey with the California Planet Search observations and update their classifications (cycling, non-cycling, aperiodic variability, etc.). The challenge is that the two activity measurements aren't entirely on the same scale, so it required a lot of checking by-eye.

Among the 55 stars with over 5 decades of observations, Anna found one star that showed particularly odd behavior: a cycling star in the Mount Wilson Survey appeared to suddenly go flat when later observed by the California Planet search!

Unfortunately, the transition from cycling to non-cycling behavior occurred during this gap in observations, setting off lots of alarm bells. Is this really the same star? Anna performed countless checks and we became convinced: as best as we could tell, this was the same star, and the data were correct. Anna published this as the best Maunder Minimum candidate to date.

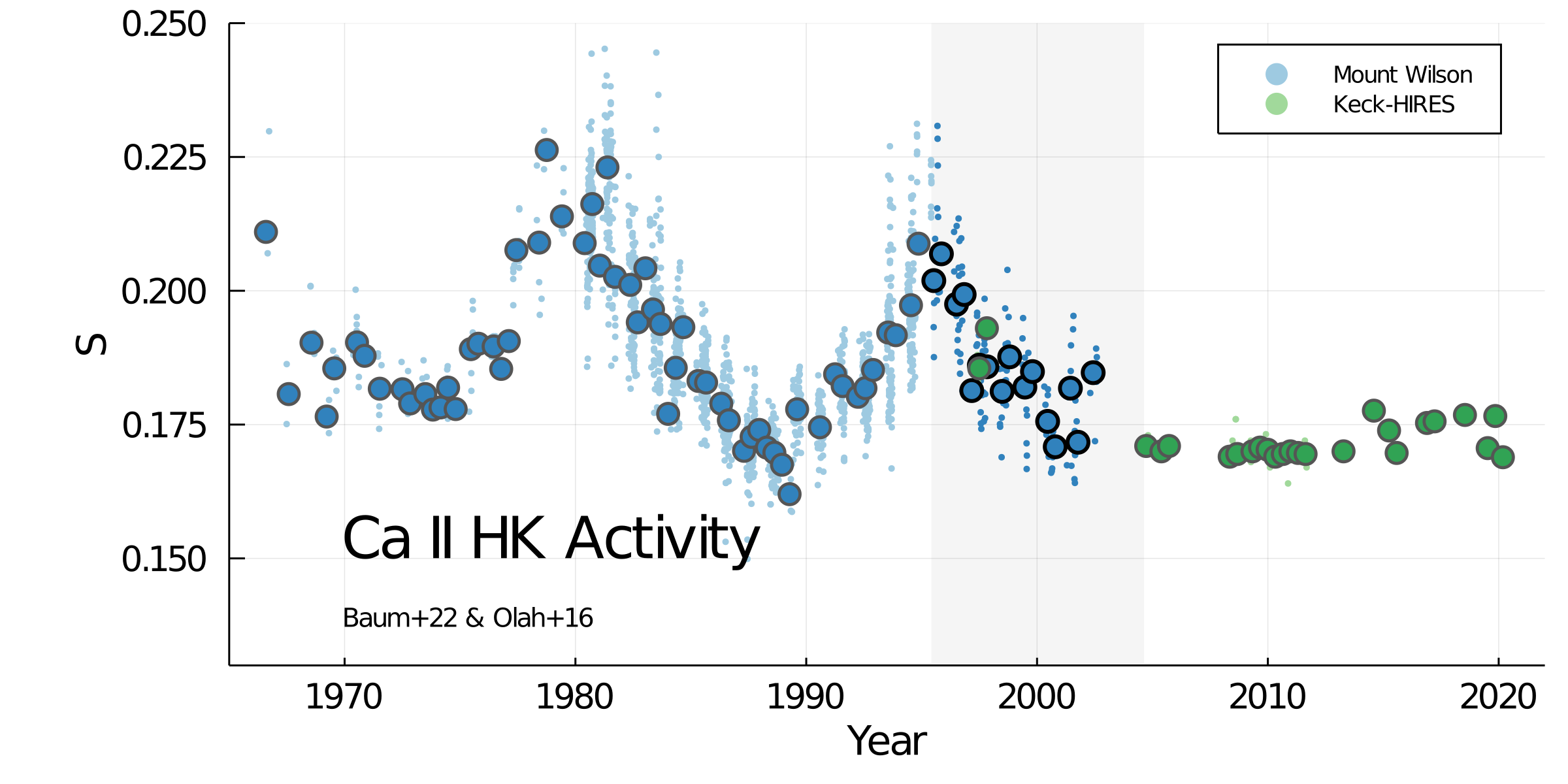

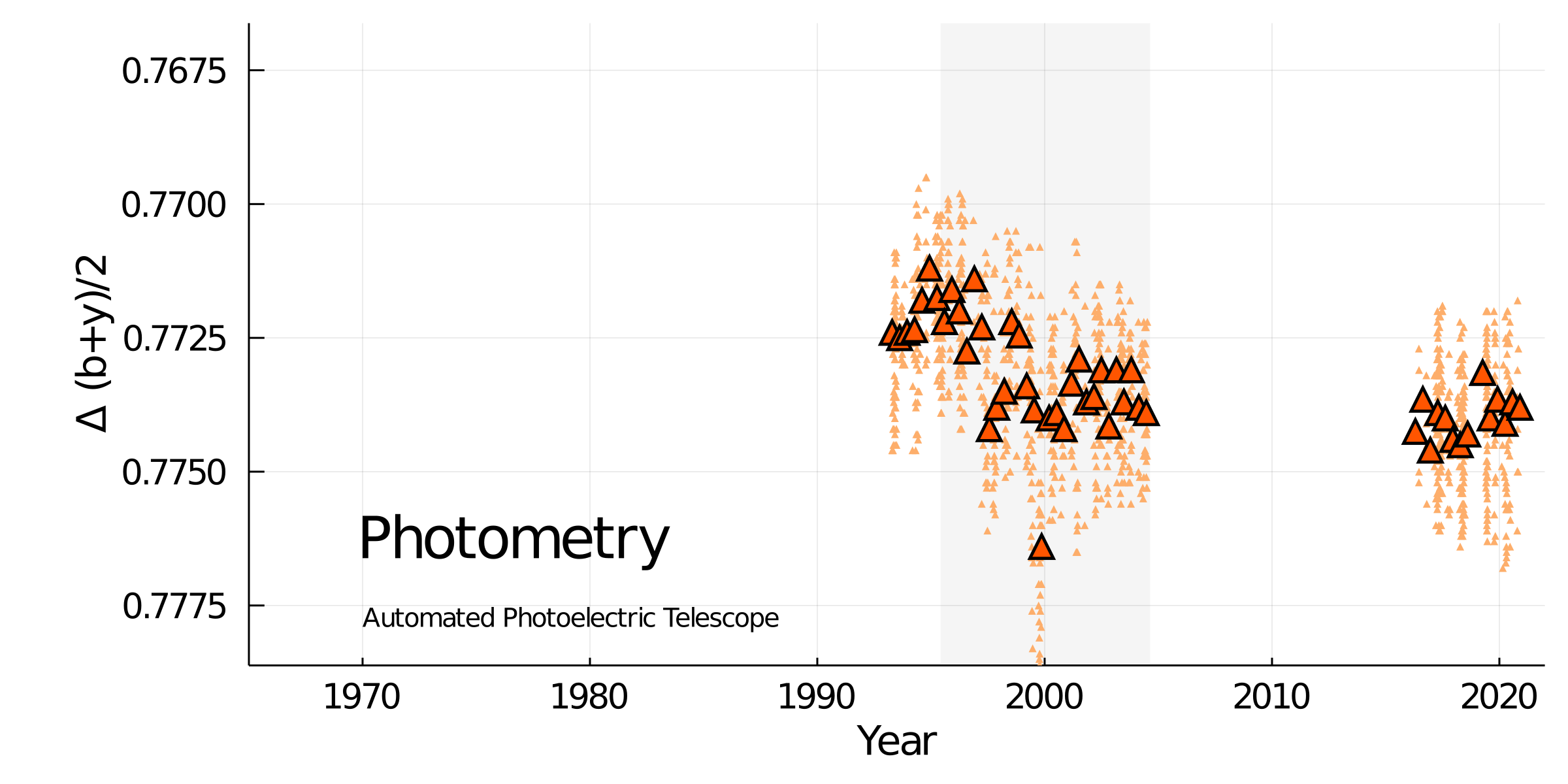

Luckily, the story doesn't end there. Upon publication, it caught the attention of others, who were equally intrigued by this star. Thanks to Travis Metcalfe, we were pointed to some additional, unpublished Mount Wilson data for this star. Additionally, we learned that this target was observed in photometry by Greg Henry's Automate Photoelectric Telescope during the crucial gap of missing data and again in the 2010s. Putting those data together was the final nail in the coffin that laid to rest any lingering concerns.

This additional data (which I published in a short follow-up letter) definitively trace out the star's transition from cycling to non-cycling behavior, cementing HD 166620 as the first true Maunder Minimum analog! With this, we can show that the non-cycling span looks no different from it's regular cycling minima (i.e., not particularly fainter or significantly "quieter"), lending credence to the idea that the Maunder Minimum is a regular part of the cycling process, with the expectation being that these spans of flat activity represent "sputtering" behavior that will increases in frequency as the star spins down and eventually becomes an old, quiet subgiant star!

Anna's discovery and the follow-up confirmation caught the attention of a lot of press. Here are some great articles about it

Now as a star on many RV survey target lists, HD 166620 will continue to be monitored in the coming decades. Only time will tell how long its Maunder Minimum will last...